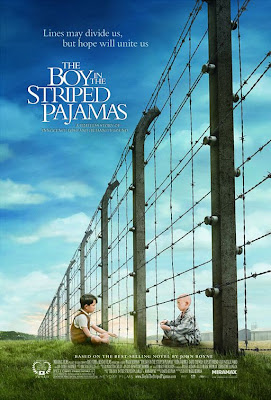

Cast: Asa Butterfield, David Thewlis, Vera Fermiga

Cast: Asa Butterfield, David Thewlis, Vera Fermiga

Director: Mark Herman

Screenplay: Mark Herman

Running time: 94 mins

Genre: Drama/History/Family

CRITIQUE

Films that tackle the Nazi systematic killing of 6 million Jews navigate the perilous waters of historical accuracy and tread the thin line between illustrative sensibility and melodrama. Claude Lanzmann, director of the renowned Holocaust documentary Shoah, once stated that “there are things that cannot and should not be represented”, a backlash targeted to Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List. This argument implies that any film touching this delicate subject is merely a partial version and that there will never be a definitive Holocaust film. Meanwhile, The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas, a recent addition to the Holocaust film canon, takes a different approach to the material, merging fable with fact, and in result creates fiction that masks a historical truth.

The real challenge of the film is how to tell the unimaginably horrific history of the Holocaust to a filmic language easily accessible by the younger generation. It is blatant that the target audience is the children demographic, since it has been distributed by Walt Disney, and since it revolves around a parable of a forbidden friendship between two children of different upbringing and race; one is a Nazi commandant’s son and the other a prisoned Jewish child. Adapted from the novel by John Boyne, Mark Herman’s narrative approach assumes the point-of-view of the main protagonist, Bruno, where his childhood exploration in a morally corrupted setting unbeknownst to him is seen and experienced through his eyes. The aim here is not authenticity but implicit imagery. There is very little of the terrifying events we know from newsreel footage that is shown here, where the imagery is metaphorical rather than upfront: a brief glimpse of the liquidation of ghettoes, a view of the so-called “farm” on a window, and a pungent smoke that rises in the air. Even the camera rarely penetrates the environment of the local Jewish camp, reminding the audience that this is Bruno’s story, not the people within, and the barbed-wire fence strongly signifies the limit to which the film can illustrate, and also stands for the theme’s division of race and classes. Where adults know the implication of these images, children will be left in curiosity.

Cinematographer Benoît Delhomme employs fluid camera movements and tints the picture with a slight golden hue, giving the film a dreamlike quality which consolidates the story’s fairy-tale approach. Long shots of around and within the large, stone countryside house are utilised to make the emotional subtext of the family living in it more reflective, and the use of spatial emptiness and walls as backgrounds in framing also denotes the distance and detachment of its characters. David Thewlis’ father, a patriarchal figure torn between family and nationalistic responsibility, and Vera Farmiga’s mother, who veers between passivity and moral awakening, are both oblivious to their own son’s exploits.

The finale, which applies cross-cutting editing, builds suspense and finally paving way to a long take of a chamber exterior that fades into black and silence. It is in this final shot where the film draws its most important point. That at the very core of this is a tale of childhood ravaged by war, and of innocence and friendship that knows no boundaries. History only serves as a backdrop, and this allegory stands for bigger moral questions about humanity and its evildoings.

VERDICT:

Forget authenticity. This is a moving, devastating portrait of childhood destroyed by war, and the power of innocence and friendship that knows no boundaries, race or differences. That haunting silence in the cinema when the credit rolls is a testament to the power of this allegory.

RATING: A-

Cast: Brigitte Helm, Alfred Abel

Cast: Brigitte Helm, Alfred Abel

Director: Fritz Lang

Screenplay: Thea von Harbou

Running time: 2 hrs 6 mins

Genre: German Expressionism/Sci-Fi

CRITIQUE:

There’s a vision that is common to the contemporary sci-fi genre, and that is the idea of a future. Fritz Lang’s incendiary Metropolis may well deserve the term “progenitor” of the futuristic cinema. It is a benchmark even today that this visionary innovation have been replicated for the nth time throughout history, and inspired the mind of Stanley Kubrick (man vs machine in 2001: A Space Odyssey), Steven Spielberg (architecture of Minority Report) and Ridley Scott (concept of replicants in Blade Runner). Heck, even Madonna made a music video about it.

Sure, Metropolis is filled with flaws. In fact, it is littered with them: there are quick cuts, contradictory scenes, images that are juxtaposed with each other, lost footage replaced by summarised templates – but to condemn it for its imperfection is just like watching The Lord of the Rings’ special effects being done by clunky HAL computers. There’s no point arguing its intermittent pace and dodgy editing for it is done in a period where cinema was just an early innovation. What’s surprising in here is that despite of the technology, there’s no mistaking for its spectacular imagery. Lang’s images are the sort that would continue slapping cinema books along the generations to come, and his technical designs are groundbreaking. See the creation on the underground city and the titular metropolis above the ground, it’s a fascinating work. It is drudgery, but one that remains historic and influential. And to note that Lang opted for a silent film epic, making full use of his German expressionistic movement and the actors’ performances, he manages to make an impact without dialogues, accompanying his stark interplay of lights and shades with social and political undercurrents. A totalitarian government overruling a toiling society, an uprising from the masses, humanity’s self-gratifying reliance on technology and mad scientists equalled with mad ambitions – certainly it is a vision not so totally removed from our own world.

VERDICT:

The earliest dystopian futuristic film showcased in retro effects during the silent-film era. Oddly enough, it works and now considered a pioneer of sci-fi flicks. Imperfect, but gloriously so.

RATING: A

Cast: Charlie Chaplin, Jackie Coogan

Cast: Charlie Chaplin, Jackie Coogan

Director: Charlie Chaplin

Screenplay: Charlie Chaplin

Running time: 53 mins

Genre: Comedy/Silent Film

CRITIQUE:

Remember when cinema was still an innovation, where movies are made without dialogues, yet they still are more capable in entertaining us than Eddie Murphy flicks – that is the magic of silent films. Brilliantly exemplified in THE KID, Charlie Chaplin (the first true worldwide star and the ultimate hero of silent cinema) and a charming little boy named Jackie Coogan team up as the Tramp and the titular Kid, and the result is an agreeable, guiltless entertainment. This was made in the time when movies are actually made for the working-classes, therefore there is nothing highbrow in this endeavour, but Chaplin’s shticks remain iconic. The plot is simply straightforward: a local tramp finds a baby abandoned in the street and succumbed to become the father of the child as he grows up. There are sequences that remain in memory: child and father pair to break-and-repair windows; the two’s daily routines in their bedroom-cum-kitchen; and the laughable separation of the child from the tramp. Because of the amusement and heightened realism of the first half, when the dream-episode comes, it becomes jarring and almost ridiculous to watch.

VERDICT:

There’s nothing more blissful in silent cinema to realise that slapstick, no matter how physical they can be, works better than recent Hollywood attempts. Chaplin does his best, but it’s Coogan that carries the film’s charm.

RATING: A-

Followers

Blog Archive

- December (3)

- November (1)

- October (6)

- August (2)

- July (3)

- June (4)

- May (4)

- April (8)

- March (3)

- February (6)

- January (11)

- December (2)

- November (7)

- October (4)

- September (9)

- August (8)

- July (11)

- June (13)

- May (12)

- April (7)

- March (11)

- February (14)

- January (16)

- December (6)

- November (15)

- October (3)

- September (11)

- August (10)

- July (16)

- June (10)

- May (11)

- April (2)

- March (6)

- February (16)

- January (15)

- December (3)

- November (3)

- October (9)

- September (8)

- August (4)

- July (8)

- June (9)

- May (9)

- April (21)

- March (13)

- February (12)

- January (12)

- December (6)

- November (25)

- October (18)

- September (13)

- August (14)

- July (12)

- June (18)

- May (8)